Benefit from Standing Back

While studying for my art degree, I was taught to frequently stand at a distance to assess my work, as I was creating it. Artists benefit from stepping back, because they can see how the whole piece is evolving, rather than getting caught up in details. That’s one reason why a painter will stand at their easel, instead of sitting: standing facilitates movement back and forth. (Of course, this can apply to drawing and sculpting, too.)

Think about what happens when you walk into a room of an art museum or gallery. Your eyes scan the work, and you find yourself attracted to the pieces with the strongest compositions and clearest elements.

It’s the same when deciding a photo’s potential: Step. Back. In between checking for focus, either view your images at small thumbnail size, or literally roll your chair away from the monitor to get a more distant view.

The Pitfall of Not Stepping Back from Your Work

Otherwise, here’s what happens: When looking closely at a photograph—necessary to make sure it’s sharp, if nothing else—it’s easy to get caught up in the beauty or serendipity of minutia.

It goes like this…

Oh my gosh, a tiny bird flew into the landscape I was shooting, and it’s sharp, and its wings are at attractive angles. It adds something special!

… or like this …

Holy cliché, Batman, check out the dew drops on those leaves (or flower petals, or insect wings). They’re sublime!

We photographers LOVE the close-up details of our zoomed-in, giant, on-screen image. You know, that same detail that maybe nobody else will notice when the image is at thumbnail size, before they enlarge it to … medium size, and maybe still don’t see the element that was screaming beauty at you (especially if the image has been compressed).

How You’ll Benefit with Distance

To benefit from standing back, look for a strong composition, either as shot, or in processing potential. Ask yourself questions like:

- Do—or will—important elements fall on the 3×3 grid lines, the rule of thirds? (If you’re breaking the rule, do so intelligently.)

- How’s the overall interplay of light and shadow?

- Have you effectively used shape and/or form?

- Does the photo offer eye-catching color harmony, contrast or highlights?

- Where does the “negative space” direct the eye?

- Do contrasts, colors, and/or shapes keep the eye bouncing around in the photo?

- Conversely, do any elements draw the eye out of the photo, never to return?

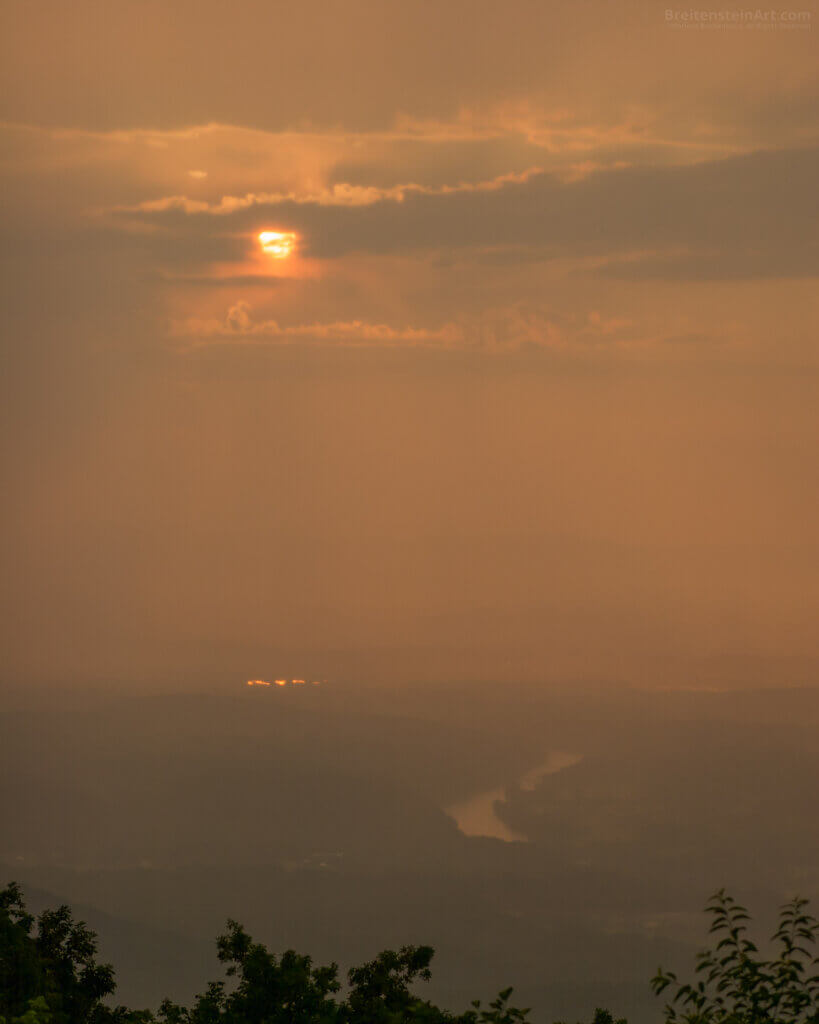

Here’s an example of the rule of thirds, color harmony, negative space and highlights:

Your Work: Small and Strong

Whether a photo is eye-catching is key. Your photo at thumbnail size must catch the viewer’s eye, or nobody’s going to enlarge it (or zoom in), to see any of the glorious details. If your photo doesn’t work at thumbnail, it’s likely not your strongest work. When a photo is muddy and the elements are rather indistinct at thumbnail size, consider whether it’s worth posting, or if you should just move on to the next.

This also applies to processing your photos. It’s a good idea to frequently step back, to see how your tweaks are affecting the overall composition.

Thanks for your time and attention, both are valuable. 🙏🏻

I invite you to view my photographs and paintings, and to learn more about me.

If you liked this post, you have options:

- Check out the art available in my shop!

- Buy me a coffee (I’d be so grateful!), or check out my Patreon (coming soon!).

- Sign up for my monthly newsletter, full of delicious tidbits.

- Follow my blog with RSS, using a feed reader like Feedly.

- Browse my other blog posts.

©Marlene Breitenstein. I welcome your inquiries about purchasing, licensing, or republishing my work. I take my intellectual property seriously. This post and its contents, unless otherwise noted, is owned by Marlene Breitenstein. It is not to be reproduced, copied, or published in derivative, without permission from the artist.